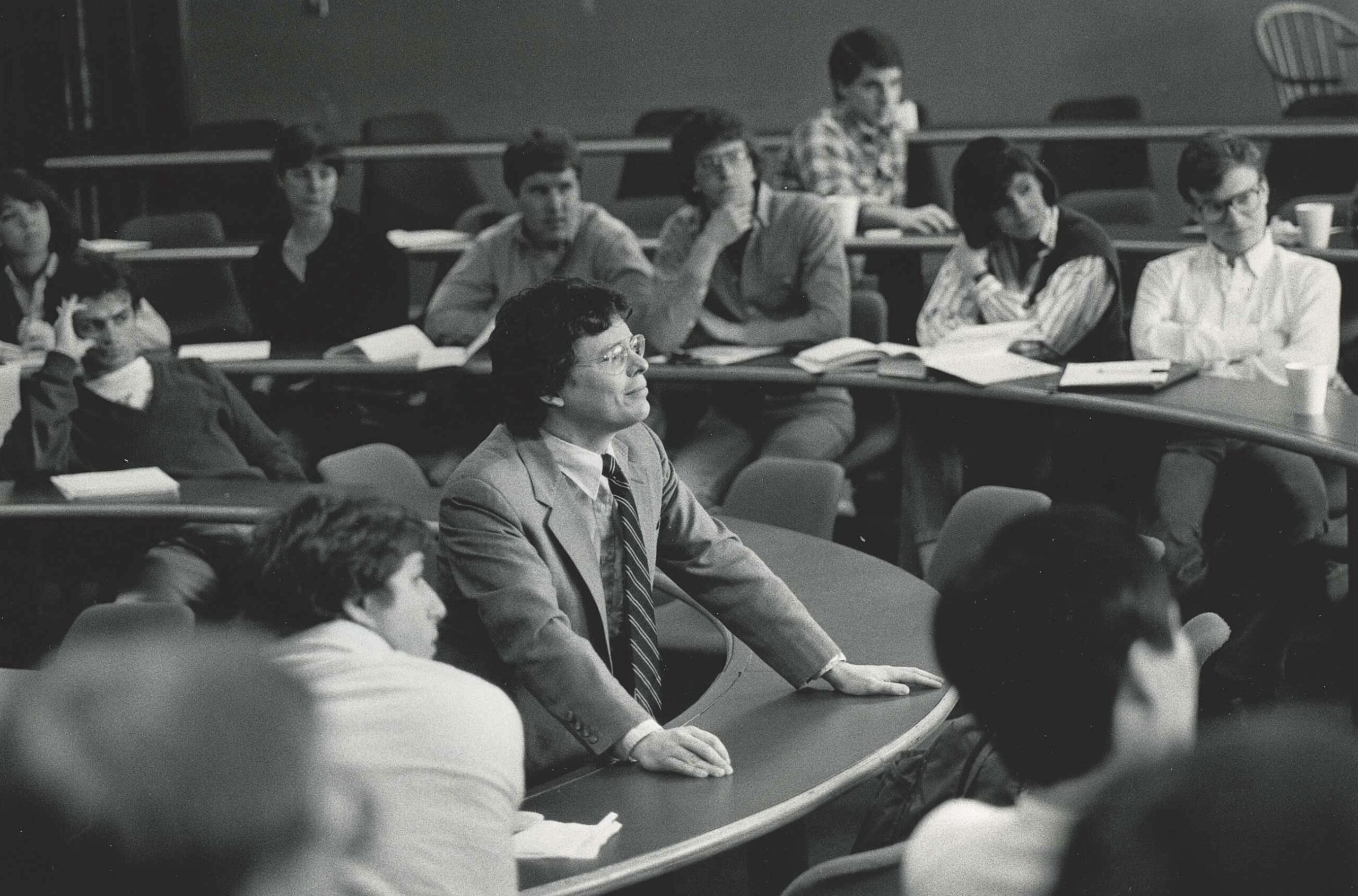

Ash: Having taught countless students at HKS and from across the university, what moment from the classroom stands out most in your memory?

Moore: I think it was one of the earliest classes I taught in the fledgling HKS executive program, around 1976 or so. We had launched our first executive program, for senior federal government executives. I was a 29-year-old associate professor with a newly minted Ph.D. in public policy and two years of government experience. And there, sitting in the front row, was General George Patton, Jr. — the son of the famous World War II general. I believe my topic was leadership! Just before I walked to the front of the classroom, Phil Heymann, my friend and colleague, said to me, “Mark, I’ve calculated that there is over 2,000 years of government experience represented in this room. I’m sure they’re dying to hear what your two years of pathetic failure at the DEA have to offer!”

A lot of what we did in the early years of HKS was trial by fire. We were building the plane as we were flying it. In those first few years, I think we learned more from the participants than they did from us. But soon we were able to give back what we had learned, packaged in ideas, curricula, and pedagogy that could actually help experienced professionals diagnose their context more comprehensively and accurately, and figure out what they needed to do from their particular positions to “create public value.”

Your seminal book in the field of public management, “Creating Public Value,” was published in 1995. How would you judge the performance of government practitioners in innovating and managing public enterprises over the intervening years?

Government managers—including those who were elected, politically appointed, or served as professional civil servants—have had a rough go of it over the last 40-50 years. They have faced political environments that made it difficult to create consistent, coherent democratic mandates for performance and operational task environments that required frequent innovations. They have been under constant pressure, with little appreciation for the difficulty of their jobs or any recognition of their successes. Despite the challenges, many were able to respond with a strong sense of professional integrity and innovative capacity.

And how do you think HKS has helped these practitioners over the years?

I like to think that we made some important contributions to these professionals, partly by teaching them some things they did not know but more by helping them understand what their combined professional experience could teach them about their jobs. There was, in fact, an incredible amount of useful and useable knowledge contained in those classrooms, and our research and pedagogic methods helped to reveal and codify it.

What has been particularly exciting and gratifying to me is that the tools we developed for use by public government executives—the concept of public value and the framework of the strategic triangle—have spread beyond government executives to include those who manage voluntary sector organizations, commercial enterprises, complex collaborations across organizational and sector boundaries, and even those who characterize themselves as “social entrepreneurs” or “social change agents.”

As a member of the inaugural MPP class at HKS, you’ve seen firsthand the evolution of the Kennedy School and graduate schools of public policy across the country. Given your near half-century of experience as a student and then faculty member at HKS, what should public policy schools be doing to better meet the needs of current and future policymakers?

The schools of public policy deliberately challenged the field of public administration as it had developed over a half century. It did so at least in part by demonstrating how the empirical tools of social science research, and the analytical tools of modelling complex systems and framing concrete policy decisions as exercises in rational decision making under uncertainty, could be brought into the practice of public policy decision-making. These efforts seemed to authorize public officials to talk about the valued ends of public policy choices, as well how best to organize the means of producing the desired effects. They also seemed to envision a government that was innovative – that was constantly looking for better ways to accomplish old missions, or new ways to accomplish new problems. What was exciting was that we had to create the capacity for strategic thinking and continuous improvement in government.

Perhaps the biggest mistake schools of public policy made over the past half-century was to over-estimate the capacity of social science, analytic methods, and maybe even “rational” thought to enable public leaders, executives, and managers to bring an unruly, uncertain, divided world to a place where it could make steady progress on important human problems. It is not that science, analysis, and rationality couldn’t help a polity understand its current condition and what could be done to improve it; it was just that polities and those leading them ran out of science long before we had a complete answer about what we should do.

I should know. I wrote one of the first doctoral dissertations in the field of Public Policy. I assumed, based on what I had learned in the MPP program, that the ultimate goal of those trained in public policy was to develop an intellectually powerful argument about what a particular government should do about a particular condition that seemed problematic. I chose as my problem, what the NYC Government should do about the problem of heroin addiction then plaguing the city in 1974. I then went to work using everything I had been taught to empirically represent the problem, to model the processes that were influencing its size, shape, location and scale, to describe various policy and program interventions that were being made in NYC and elsewhere and evaluate their impact, and to recommend a “dynamic strategy” involving multiple interventions developed and deployed over time to reduce the seriousness of the problem. Two years, and 800 pages later, I was not finished. I felt crushed because it seemed as though the promise we had made to ourselves and to our students could not be fulfilled.

I have spent the rest of my career trying to develop an approach to leading and managing varied initiatives, launched by different individuals, from different platforms, in different contexts, that have a plausible chance of improving social conditions. Science, analytic methods, and a constant struggle for rationality in the face of conflict and uncertainty are an important part of this effort. But I keep finding that there has to be more space created in our hearts, minds, and actions for what could be broadly described as humanity.

My friend Phil Heymann, once again set me, and to some degree, HKS straight on this matter. He used the word CHILE to point to a vast domain of human knowledge that was essentially left out when the modern HKS started on its venture to improve governance around the world. The word stood for Culture, History, Institutions, Law, and Ethics. These describe the elements of human life and efforts to understand the risks and opportunities of living interdependently in a particular place and time that are essential to making not only rational, optimizing decisions, but also engaging in humane, just conduct towards one another. It is the later that has to be the goal of governance, even as we pursue that goal through government using science, analytical methods, and rationality of a particular kind.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.