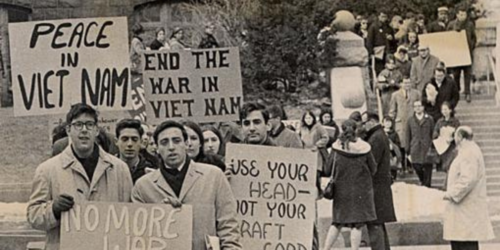

In 2020, the United States bore witness to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests that arose in the wake of the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and, most prominently, George Floyd. BLM protests have been cited as among the largest organized demonstrations in recent US history as Americans and world citizens alike protested police brutality, anti-racism, and called for substantive institutional and legal shifts pertaining to policing. What was the impact in the state of Connecticut?

From May 31 to December 31, 2020, 105 of Connecticut’s 169 towns held at least one protest, with some towns hosting multiple events. In total, there were 316 protests listed in the data of the Crowd Counting Consortium (CCC), with many events being concentrated in a few, specific towns. The towns that saw the most anti-racist protests were Southbury with 33, Hartford with 29, New Haven with 27, Bridgeport with 16 and Stamford with 14, all together accounting for about 37% of all Connecticut anti-racism protests listed in CCC data for that time period.

On that list, Southbury is a notable anomaly, with the town of just under 20,000 accounting for the highest concentration of demonstrations. The anomaly can be attributed to the consistency of social justice group, Justice for Southbury, in holding anti-racist demonstrations on a weekly basis from late May to December of 2020. It is also important that the media reported on the weekly protests so that CCC could gather the information; the press may lose interest in weekly events, especially outside of major metropolitan areas.

While all the aforementioned demonstrations can be broadly categorized as anti-racism protests they generally differed in terms of the resulting impact of individual demonstrations. The evidence of impact is mixed, with some of it demonstrating a correlation between a protest and outcome and other stronger evidence substantiating a causal tie.

In New Haven and New London, demonstrators called for the removal of each town’s Christopher Columbus statue. In both cases, protest organizers argued that Christopher Colombus represented a deeply racist and colonial history of America and that honoring him with a statue was deeply offensive to residents of color. New London saw a series of demonstrations over late May and early June 2020 calling for a series of changes, including the removal of the Columbus statue. After multiple demonstrations and one in which a group of youth activists vandalized the statue, the Town Council voted to remove the statue on July 16, 2020. Statue removal occurred similarly in New Haven as demonstrations and instances of vandalism led to the New Haven City commission voting to remove the statue on June 24, 2020. In both cases, it is evident that the advent of anti-racism protests in 2020 were crucial and consequential in both statues being removed.

In two other examples, the evidence is suggestive that protests led to policy change: the passage of the 2020 Police Accountability Bill and the simultaneous efforts to implement police reform in Connecticut. We see a correlation between the protests and the policy changes that followed. Despite being initially spurred by the killing of George Floyd, the Police Accountability Bill began to receive support from demonstrators in Connecticut in various ways. A Fairfield protest in June 2020 specifically called for House Bill 6004 to be passed through the Connecticut legislature. Protests in other towns, such as New Britain called for measures that ended up in the bill, such as the expansion of body camera use. These two demonstrations demonstrate preliminary evidence of a link between Anti-Racism demonstrations and the passage of the 2020 Police Accountability Bill. But we do not have enough evidence to state with certainty that they are causally linked.

In addition to protests that actively called for legislative action on police accountability, Hartford began to implement police reform in the wake of demonstrations. In June 2020, the city voted to “reduce and reorganize” the policing budget after days of demonstrations calling for reduced police allocation in favor of funding social services. While there is evidence to suggest a correlation between Connecticut demonstrations and police reform, there is not yet enough to suggest a causal link.

A key recognition we made is that in a few of these towns, Bridgeport, New London, Hartford and New Haven in specific, there were several demonstrations that occurred pre-2020 that laid the groundwork for policy changes and implementation. For example, all of these towns saw demonstrations, relating to the death of Jayson Negron, police brutality, and police reform stretching back months and years prior to May of 2020. This suggests that the history of protests allowed time for these demands to spread and develop within individual communities. Previous protests raised people’s consciousness about the issues.

This research is preliminary in establishing the true range of impacts that anti-racism protests in 2020 have had on Connecticut. It also opens future avenues of research that can be further developed through a closer analysis of those demonstrations through interviews, research into related government documents, and the systematic assessment of police reform and policy changes that were spurred on and inspired by anti-racism demonstrations.