Jay: You are listening to the Nonviolent Action Lab Podcast. I’m your host, Jay Ulfelder, he/him. Together with Harvard Kennedy School professor, Erica Chenoweth and other members of the Nonviolent Action Lab team, each episode we bring you the latest research, insights and ideas on how nonviolent action can or sometimes fails to transform injustice.

It’s Wednesday, June 12th, 2024, and today we’re talking about Atlanta’s Cop City project and the movement to stop it. I’m joined by Joseph Brown, associate professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Boston. His research focuses on political peace and conflict, including protest movements, armed rebellion, and state responses to dissent. Joe, thanks very much for making time to talk today.

Joseph Brown: Thank you very much for having me. It’s good to speak with you.

Jay: So let’s start with the basics. What is Cop City?

Joseph Brown: Cop City is the derisive nickname for a proposed police training center to be built in greater Atlanta. The project dates back at least as far as 2017. It’s the brainchild of a very powerful police lobby called the Atlanta Police Foundation, which wanted to build a facility to be the new state-of-the-art police training center for law enforcement in the greater Atlanta area, and to some extent nationally too because it would also train people from elsewhere in the country and even be a site for international collaborations between law enforcement in Georgia and counter-terrorism professionals in other countries.

Jay: And what about the movement to stop it? When did that get started? Did that kick off pretty much as soon as the project was announced, or what’s the trajectory there?

Joseph Brown: It’s a really interesting one. So the plans for Cop City go back to 2017, but there really wasn’t public discussion about it until 2021. So in the intervening time, there was the 2020 Racial Justice Uprising, all of these street protests nationally, a national conversation about racialized police violence being a real vivid humanitarian emergency in the United States. Every year, police in the United States kill somewhere on the order of 1200 to 1300 people, and the number been going up and up. 2023 was the worst year on record, and before that, 2022 was the worst year on record, and before that, 2021 was the worst year on record. Even post 2020, the numbers keep going up and up and they are highly skewed racially. One would’ve thought that after all these 2020 protests that more serious action would be taken at the local level on the issue of violent policing and what it does to communities of color in Atlanta, which I think is the blackest major city in the United States.

However, the response of the Atlanta Police Foundation and the government in Atlanta to 2020 was to approve a plan for a new police training center, which would be built in the midst of this 70% Black neighborhood, predominantly poor and working class that really doesn’t want the project there. There’s not a lot of evidence of public support for putting it there. And that neighborhood already absorbs the things that the City of Atlanta wants to dump into somebody else’s backyard essentially. It’s a neighborhood in unincorporated DeKalb County, so they can’t vote in Atlanta’s elections. It’s on a parcel of land that was formerly a slave plantation and then a prison farm. It’s in a neighborhood that already hosts the old garbage dump, two prisons, one for adults, one for children, a sewage treatment plant that is overtaxed and overflows in even a modest amount of rain.

And if you’ve spent time in Georgia in the summer, you know you get more than a modest amount of rain anytime it storms, it’s a very humid, very stormy place. And the neighborhood already hosts two other police facilities, two different firing ranges. There’s a SWAT team facility across the road that has its own rifle range and the bomb squads rehearse bomb disposal like controlled detonations there. There’s also a shooting range in the Atlanta Forest itself. And this neighborhood just absorbs environmentally the things that Atlanta doesn’t want, socially the things that Atlanta doesn’t want, and psychologically, ’cause imagine that you’re a kid growing up in a neighborhood where there’s just constant sounds of gunfire and what that does to you psychologically. Or as an adult.

When I say Atlanta doesn’t want them, I think I should explain that a little more. The affluent, privileged and whiter parts of Atlanta want a cop city to be built. The project is actually somewhat popular in neighborhoods like Buckhead, a much whiter, wealthier demographic live in this neighborhood, and they’ve been complaining post 2020 about a supposed uptick in crime and how the city’s leadership have failed to prevent it. And so there is some support for Cop City, but it’s not being built in Buckhead because people with those privileges and influence, I guess are able to find ways of having these things built in somebody else’s backyard yard.

I think you should talk about environmental racism when discussing Cop City too. So as I mentioned, that neighborhood already has the old garbage dump and the sewage treatment plant, and that plant backs up their water quality issues, you can smell it in the air. And imagine cutting down… There’s about a square mile or originally there was about a square mile of forest there. This area is called the Atlanta Forest or the South River Forest. It’s also described as one of the lungs of Atlanta, and it serves these important ecological roles of absorbing excess rainwater and holding the soil in place ’cause it’s all this really rich, red Georgia clay, but clay gets very slippery in water and it runs downhill, and those trees’ roots absorb rainwater and hold the clay in place so that the sewage plant doesn’t back up more and the creek doesn’t back up more.

There’s a literature on environmental justice in the United States, and people have been noting for years how these kinds of things get cited in communities of color. They get put in neighborhoods where people of color live, where people with lower income levels live and they have to pay the costs, the environmental costs, and I guess the psychological costs and the costs to their home values of these things. And this is another case in point-

Jay: Mental costs in many cases as well, yeah.

Joseph Brown: Yeah. There’s studies out there that communities that have more trees and more parks have better mental health outcomes and also lower crime rates interestingly. And causality is complicated, but it’s really interesting that this is a debate over policing and crime. And what’s being done is that this neighborhood that has a forest, and forests are associated with less crime and they’re going to cut that down. It’s another thing that’s being taken away from them.

You asked about the movement. So when the plans for Cop City finally were surfaced, due to a certain amount of muck raking by people who pay close attention to local city politics, and people made a stink about this. They said, “Well, why is this year response to 2020? You want to build this facility.” It’s called Cop City because it’s designed to include a simulated urban environment for the rehearsal of various police operations, ostensibly including riot control. Why is that your response to 2020 and the racial justice protests? A lot of people were asking that question and metaphorically banging on the doors of City Council and City Council agreed in the fall of 2020 and things were still locked down to some extent then, it was the peak of the pandemic.

City Council, I think probably didn’t want people literally banging on their doors either. And so they said, “We’re going to open a voicemail and you can send comments to us. Record your message about Cop City. We’re interested in hearing your voices.” And people did just that, and they ended up with 14 hours of public comment in the form of voicemails from hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people, and some local researchers listened to all the audio. City Council listened to it, and it took them two days of just sitting there listening to all these messages and local researchers listened to them too and determined that about 70% of them were comments against leasing this land and authorizing $30 million of city money to build this facility.

The price of the facility in total is $90 million, and the original plan was for the Police Foundation to raise 60 million in corporate contributions from big companies like Home Depot and Wells Fargo, Coca-Cola, Amazon, and then the city would put up $30 million. And you had 70% of the callers saying, “Don’t do this. Don’t put 30 million of city money and don’t lease this old prison farm to build this here in this neighborhood.” And you would think that in a high functioning democracy, if that’s what one has, that City Council would perceive a 70% mandate against doing a thing and then not do the thing ’cause clearly people don’t want it. And they basically just ignored that. They authorized the funding and the leasing of the property anyway and said, “All right, let’s go ahead and build Cop City.”

And when that happens, I think if you’re a community activist, you have a few choices. First of all, you’re exceedingly angry that you’re being ignored. You can have some questions about whether government is being compromised by… The Police Foundation has a lobby, a very powerful lobby that lawmakers, that mayors that city counselors are afraid to go against ’cause it does have the power to come out against them in their next reelection campaign. And then you might think, okay, well, what do we do? What are the strategies and tactics we can employ to try and get justice here and use this land for something else and use city money for something else and not build what people were calling at this point an urban warfare training center for Atlanta police?

So some people kept doing the very much within the lines of legality strategies. They didn’t stop going to City Council meetings and they would go to planning meetings, like planning board meetings. They’d show up at events that the mayor was doing, ribbon cutting ceremonies and try and talk to the mayor. They went out canvassing in the neighborhoods that would be most affected, trying to raise awareness and say, hey, do you know about this? This is going to happen. Come get involved in this campaign to stop Cop City. People did marches, people held signs, people did all of those things, and other people looked for other ways of plugging in too and started doing things that fit under the broad heading of direct action. And direct action can encompass many different things.

David Graeber has a book about this, and I’m not quoting exactly, but he says something along the lines of everything from sitting at a segregated lunch counter to setting fire to one can be included under the heading of direct action. And people did a wide spectrum of things. In the fall of 2021, a thing that people started doing was occupying the forest itself, just physically inhabiting the forest. And while being mindful of time, I’ll just try and describe the forest itself for a moment here. It’s actually two different properties. There’s about a square mile or 380 acres or so of land called the Atlanta Forest. The western portion of that is the old prison farm, and it’s owned by the City of Atlanta. And then there’s this creek, the one that overflows and has the sewage runoff problems, Intrenchment Creek.

To the east of that is a parcel of land called Intrenchment Creek Park, which was donated to unincorporated DeKalb County with a stipulation that it be used as public parkland “in perpetuity.” That’s what the donation says. That part of the forest is threatened by a separate development project. There’s this local Hollywood mogul who wants to clear cut it and build a sound stage for his cinema production company, and he brokered the corrupt behind the scenes land swap with DeKalb County’s government where he traded them an adjacent plot of just dirt land that he had already cleared, thinking he could build a sound stage on that land and it turned out it was too swampy and he couldn’t build it.

And so he went to DeKalb and said, “Let me trade you this dirt plot for this beautiful green public park that people are already using ’cause it has jogging trails and running trails and a parking lot and a little field for people to fly radio-controlled airplanes.” And for some reason, DeKalb’s government agreed to this. But because people sued them and tied the land swap up in court, that half of the forest remained an open public park that the community was still using and you could occupy it with relatively low risk. Put relatively in big scare quotes ’cause we know what happened later on in that park, but it had a parking lot. You could drive in a bunch of tents, you could put up infrastructure there to support life.

People created a little utopian forest village in Intrenchment Creek Park and they erected tree sits, which is this classic, environmentalist, nonviolent direct action tactic where you essentially use arborist or mountain climber equipment and get 40 or 50 feet up in a tree and build a platform and you live and sleep on the platform ’cause you are a very brave person. You trust in the knots that you have tied and in the fact that you’ll be able to sleep on that platform and not roll off of it in the middle of the night. People did that. They built a forest encampment with… It was this utopian vision of what a stateless property-less society might look like. There would be free food distributions. Local charities that give away free food to people who are food insecure would meet there and give away food every Wednesday.

People built a free cafe. They had music festivals. They had free tent housing for anyone who was unhoused. And it became a magnet or a queer anarchist utopia in a forest in the middle of a major US city. At the same time, people were doing other forms of direct action too, and they had been pretty much from the very beginning. As early as April or May of 2021, excavators and construction equipment in the vicinity of the Atlanta Forest began to have mishaps and failures, and there are credit claims for some of these things. People saying, “Hey, this excavator was going to be used to clear this forest land either to clear it for the soundstage Hollywood guy or to clear it for the Cop City project and we disabled it.” And in some cases, people set fire to excavators or feller bunchers and things like that.

So there was that form of direct action as well. And I think that the movement, in the absence of a formal organization, ’cause there is no formal Stop Cop City Organization and there’s no formal Defend the Atlanta Forest Organization. It is an anarchic coalition of different people and different groups that are all plugging in in different ways that feel comfortable to them and contributing in their own way, especially in a forest occupation that has a sizable actual anarchist component where people are averse to hierarchical organizing and no one really wants to tell anybody what to do, like, these are the official tactics and don’t go beyond that. There isn’t a leadership cadre.

People using those sabotage tactics and people using the more traditional tree sit, nonviolent direct action tactics and people using the above ground canvassing and City Council speak outs tactics all learned to coexist even though they used tactics that other people might not use and other people are using tactics that I as individual A, might not use. But I think they learned that everybody contributed something unique and it was better to get along even in moments where people might disagree about a particular tactic and whether it was advantageous at that moment.

Jay: So how did the police and the city government respond to all this?

Joseph Brown: Well, things developed over time, and I think they became more violent over time, not on the part of the protesters. The protesters hued to what their own notion of nonviolence is. And it’s not the conventional notion of nonviolence that I think people think about in the literature. Or if you’ve read about nonviolence, you’ve probably encountered this idea that things can be contentious, but they can’t get destructive. And the notion of nonviolence from Stop Cop City is pretty different from that. Things, as long as they don’t injure people, were considered nonviolent by most people in the woods. So those sabotage actions were not considered violent because they decommissioned an excavator, but excavators don’t have feelings. And I think people were much more concerned with the violence of police, and that really escalated over time.

The first big SWAT raid happened in May of 2022. It was a multi-agency SWAT raid, I think led by police at the local level as opposed to the state level, although I could be wrong about that. And federal authorities were there too. Police first drew their guns on protesters during that raid in May of 2022, and there is scanner audio recordings of them discussing possible justifications for using lethal force against protesters who threw things at them. I think things settled down a little bit. In the summer of 2022, there were a few raids. I think police announced publicly that they were going to try and crisscross the old prison farm twice a week, and so there would be these little mini raids. Meanwhile, protestors were having these week of action events where they would open the woods up and invite hundreds of people in to come to free music festivals and build forest infrastructure, and to involve the broader Atlanta youth community.

You want to get youth involved, well, have a free rock music show and a free rap show and the kids will show up. And at those times, there would also be police shows, of course, like helicopters circling the woods for hours or small surveillance airplanes circling the woods for hours. Things got dramatically more violent in December of 2022, and it’s not really ’cause the protesters changed anything that they were doing. The forest occupation continued more or less as it had been. There’d be little tussles sometimes. The Hollywood guy would sometimes send in a bulldozer to try and clear trees and he would get chased away ’cause a bunch of people wearing camouflage and face masks would come out of the woods and throw rocks at the bulldozer people until they had to run away. So things like that would happen.

But I think that when the forest canopy came down in the fall, it became much easier for police with their advantage in air surveillance in the form of these military surplus technologies that are on drones and helicopters, all this infrared vision stuff, it became a lot easier for them to map the forest infrastructure and very difficult for people to hide from them. And in December of 2022, a massive multi-agency raid went into the woods, and it was dozens of police with body armor and long guns. They were wearing olive drab. They had multiple armored vehicles including this thing called The Beast. It says, “The Beast” on the front of it. You can find video of all of this. Again, I’m not breaking any news.

And over the course of two days, police snatched up five or six people. They fired teargas and pepper balls up into the trees to try and get the tree sitters. And that’s a very dangerous thing to do ’cause if you fire teargas upward, you risk hitting someone in the eye with a teargas canister. There are some allegations that police actually fired warning shots using live ammunition from their sidearms. I’ve heard people say that. There’s some video of people alleging these things too. And the people who got plucked out of the trees were charged with domestic terrorism under a very expansive Georgia state domestic terrorism law, which in just a really weird twist of history was passed after a White supremacist named Dylann Roof gunned down Black parishioners in a church in Charleston, South Carolina.

So a lot of well-meaning people thought, well, we need to make domestic terrorism like that illegal in Georgia. But unfortunately, the first time anybody has used that law has not been against White supremacists, it’s been against racial justice protestors. So that raid was very frightening. There was a press conference, which almost didn’t happen because police tried to cordon off Intrenchment Creek Park as the press conference was happening. And you can see these videos online of people getting chased away by cops with pepper ball guns out of a public park during daylight hours. But people had their press conference and they wondered out loud, how long is it going to be until police actually shoot someone with live ammunition ’cause it’s escalating and escalating and escalating?

But people still filtered back into the woods. They tried to rebuild the protest infrastructure. They built new tree sits, even though the old ones, these beautiful old growth trees have been cut down. And I think the next really significant event, and people don’t talk about this one quite so much, but Brian Kemp, governor of Georgia tweeted out this statement in early January, touting those December raids and saying, “We’re not done.” I have it in front of me. It says, “Rest assured, they will not be the last steps we will take.” Or, “Rest assured, they will not be the last (terrorists). We will take down as this project moves forward.” And he promises swift and exact justice. And he says, “We will bring the full force of state and local law enforcement down on those people.”

Which it reads like he’s about to tell the state authorities to go into the woods and crack heads. And then on January 18th, that’s exactly what they did. The next task force was led by Georgia State Patrol. They went into the woods early in the morning. They surrounded the campsites in Intrenchment Creek Park, sites that were really deep in the woods that were usually safer. And they surrounded the campsite of a forest defender who had been camping there and living there since May of 2022, a person who went by the forest name Tortuguita, sometimes shortened to Tort. They were a longtime occupant of the forest, a queer, non-binary indigenous descendant, anarchist born in Venezuela, who more recently had lived in Tallahassee, Florida, who had gotten involved with union organizing with the international workers of the world, the Wobblies.

Had been involved in Food Not Bombs, which is this anarchist institution that makes and gives away free food to people. They were a protest medic. They were very interested in training other people to be protest medics. And they were a person who had been the welcoming crew in Intrenchment Creek Park when people first arrive, and that includes journalists. There’s interviews of Tort that you can find online by journalists who approach them, and they’re very personable and not especially worried about talking to journalists. They’re pretty brave about that. And so they were this person who did a lot of meet and greet work and a lot of what you might call reproductive labor in camp, like making sure people are fed and housed. And also a conflict resolution person when disputes arose in camp. They were a conciliator, which is necessary in a social movement that includes people of many different inclinations.

Unfortunately, they slept in that day as they often did, and they woke up to six Georgia State Patrol officers surrounding their camp, and we don’t know exactly what happened next. Police have refused to release their full files on whatever happened next, but we do know that police opened fire and killed Tort in a hail of gunfire, not to put too fine a point on it. And they became the first environmentalist protestor shot dead by police in the United States. You could define environmentalist a whole bunch of different ways, and there’s other people who might also be able to claim or you might be able to claim as the first environmental protestor shot dead by police. But it was a real watershed moment, and I think it was not surprising to people who were close observers of the movement that police killed somebody. I think it was very surprising how they killed because…

So I have been writing a book on intersectional, environmental and racial justice movements for the last couple of years, and hopefully it will come out next year. And I interviewed Tort ’cause Tort was a person who gave interviews. And we talked a number of times and became pretty friendly. Everybody was friends with Tort. They were a very friendly person. And I had asked them a few questions about race and direct action because some things are safer to do if you’re a White person, and Tort was not a White person. And interfacing with police, if that becomes necessary, is not a thing that they felt safe doing. And they specifically told me on a couple of different occasions that when police come, they prefer to go back deeper into the woods and take shelter and let White comrades come forward and have those interactions with police.

So it was just very surprising to find out when it finally came out who police had killed because it was someone who really did their best to avoid ever having law enforcement interactions because they knew how unsafe it could be. It was just a real surprise.

Jay: You think the intensity of the police and governor… You’ve got the governor tweeting something, like you said. Do you think there’s a connection between that and the 2020 uprising or do you think this is just how Georgia and Atlanta governments react? I can imagine we’re still inhabiting this backlash against the Racial Justice Uprising of 2020. It’s just striking why this project has been deemed so important despite the issues you’ve mentioned of public dissent and various forms and the danger that the police response to this was putting people in. I wonder if you think there’s a connection there or this is just something you would’ve expected whether or not we’d seen the uprising in 2020.

Joseph Brown: I think that I expected the legal repression against this movement. Some of my previous research has been about an older generation of radical environmental groups that got slapped with the ecoterrorism label back in the late ’90s and early 2000s. That was really the last time there was a lot of sabotage. Not a lot, but notable acts of sabotage that were claimed by radical environmentalists. And what was done by the government was this massive investigation called Operation Backfire. There are people who are still in jail from that. I expected that sort of thing to happen, and people talked about that. Actually, I asked Tort about that. I have my interview notes here, and it’s a thing that came up and they basically laughed it off. They said, “Oh, it’s a scare tactic.”

But that’s the kind of thing that you expect, people using the T word and big scary sentences to try and intimidate social movements into packing up and going home. I didn’t expect to be preparing for my January 2023 class on terrorism that I teach and then the day before, reading that police had actually shot someone dead in the woods for camping. And it’s hard to say whether it’s linked to 2020 or not. I think police militarization is a serious problem. I think the teaching of violent tactics to law enforcement to deal with nonviolent situations is a very serious problem. And I think that impunity is a very serious problem. After police killed Tort, they issued a whole bunch of self exculpatory stories, saying, “Oh, this person came out and fired on us with no warning.”

And then they had to walk back away from that ’cause clearly that wasn’t sticking and then they came out with a few other stories. And now the one that they’ve settled on is that they had some kind of exchange of gunfire with Tort, which anybody who knows Tort would know that that’s the least likely thing that they would ever do. You never know completely, but there’s been this character assassination campaign of selectively releasing parts of Tort’s diary and fixating on the edgier things that an anarchist in their twenties might say in a diary and stringing them together to create this image of police responding with, as their own self investigation called it, objectively reasonable levels of force to a dangerous activist.

And I don’t know how shooting someone 57 times is subjectively reasonable, especially since the autopsies show that their hands were raised and there was no gunpowder residue on them. That is a problem. I think it predates 2020. And I think as important as it was to do all those demonstrations, the work is clearly not done because the problem is only getting worse, and I think part of it is impunity.

Jay: I guess there’s been, in addition to this trend in increasingly aggressive police actions around the forest and the movement more broadly, also an escalation of the law fair side of that more recently. Can you talk a bit about that?

Joseph Brown: So after the December raid and the January raid, police made these arrests and the initial charge was domestic terrorism against the people they arrested. There were follow-up demonstrations in January and in March of people who were protesting specifically the killing of Tortuguita, and there were also arrests made at those and the charge was terrorism. And then there was this gap in time, and there was this rumor going around that the Georgia Attorney General was trying to string all of these people together into a racketeering prosecution under the same law that was used to indict Donald Trump for election malfeasance in the State of Georgia.

It turns out most of the people who were initially charged with terrorism have not been indicted for terrorism, a few of them have. But the big indictment that came down out of that same grand jury that indicted Donald Trump was a racketeering indictment with 61 defendants, and many of them have very plain vanilla offenses listed in that indictment. It basically relies on this legal theory that if you’re in a social movement and someone else does something illegal in the social movement, you are responsible for it because you’re part of a criminal conspiracy. The indictment alleges that there is an organization called Defend the Atlanta Forest that organized all the protests. That’s just an obvious falsehood, there is no such organization. And I think it’s a real distortion of how that movement has organized.

It’s a decentralized social movement. There’s no central hub, but they’ve used the racketeering law that was initially designed to deal with centrally organized criminal mafia type groups and applied it to a social movement. And people whose contribution to the social movement as alleged in the indictment was buying food or buying medical supplies or buying camping supplies or writing an anti-police slogan have been pulled in as criminal conspirators of an alleged racketeer operation. And the penalty for that in Georgia is from five to 20 years in prison. So if you’re trying to chill social movement organizing, regardless of what your notion of violence or nonviolence is, there are people in this indictment who are looking at a 20-year felony for buying glue to make a protest sign, I assume, or writing the slogan ACAB on their arrest paperwork in place of their name.

There’s someone who’s facing a 20-year felony for writing ACAB, which is First Amendment protected activity, but with this law and this nascent legal theory that’s being crafted, it just gives people who want to be authoritarian a lot of power to crack down on social movements that criticize them.

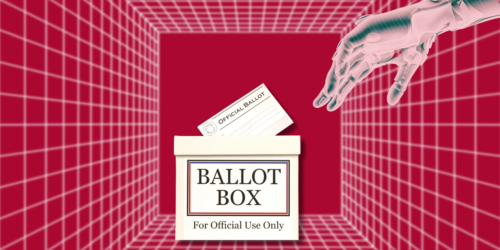

Jay: Part of the politics of this has been folks in the city government and others in civil society, whatever you want to call it, who support the project saying, “You’re doing this the wrong way. The problem is you got to do this the right way.” And so there has been an effort to put the, is it the city funding for the project, on the ballot? And I gather the city’s been a bit hostile to that. Can you talk a little bit about that, the ballot initiative and where that stands?

Joseph Brown: I can. I’m smiling and I’m laughing a bit as you say this because the idea that people doing it the right way were going to get a different response. I had a conversation with someone who’s a writer from Atlanta and who’s a friend now, a friend of mine. And we were joking like, “Yeah, when you’re doing it the wrong way, they say do it the right way. And when you’re doing it the right way, they say there is no way.” So after these real violent crackdowns on the forest occupation and the closing off of the forest in March of 2023, there’s a police cordon around it now. Every 100 yards, there’s a police vehicle. You really cannot do forest occupation there the way people have been doing it. People in the movement put their heads together and said, “Okay, well, what can we do?”

And with all of the national attention and the sympathy from the police having gunned down a young queer person of color who was just sleeping in a tent in the woods, you had big environmental groups come out in favor of the protesters, including the ones who were facing terrorism charges for destroying property, the Sierra Club, other environmental groups. You had really big mainstream venerable civil rights organizations like the NAACP come out in favor of the protesters and really not say peep about the protests needing to remain peaceful. They did a really good job, the people in the movement who reached out to them, of encouraging them to contribute in the ways that they felt comfortable. And if some tactics maybe made them a little less comfortable, to keep those disagreements out of the public discussion.

You had the American Friends Service Committee, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, local religious organizations like the Parkside Baptist Church, not exactly a crowd of hardened anarchists, all coming out in support of this movement of feral queer anarchists who had been running around the woods, living in tents and eating trash to stay alive, more or less, people eating out of dumpsters. And these big groups were like, “We sympathize with them. Yeah, they’re a little rowdy, but what the government has done is just so above and beyond. Let’s focus on this outrage and ending it.” And they lent their resources to this massive canvassing operation. They trained people to canvas. Local groups got together, taught people that canvas.

There’s a provision in the law that allows people to put referendums on the public ballot in Atlanta if you collect enough signatures on a petition. And so when you get big mainstream groups like that organized, they can collect a lot of signatures. And they collected 116,000 signatures, which is more signatures than the current mayor of Atlanta got votes to put him into office. So this is a very powerful signifier of public opinion, and I think it was very frightening to people who were very much out in front in public in favor of the Cop City project. And so what the City of Atlanta did was not to put this on the ballot, they filed a bunch of legal challenges alleging that the referendum is illegal, challenging who’s allowed to collect signatures, challenging the timeline for the collection of signatures.

They took it to court. The judge made a ruling. People collected the signatures and followed the rules the judge laid out and submitted them by the deadline the judge gave them. And then the City of Atlanta challenged that too and threw this whole thing into a legal limbo. And I think they’re essentially trying to run out the clock. If they can keep it in court and refrain from counting the signatures, ’cause they’ve refused to count them while the court cases are working their way through, they can clear as much land on the old prison farm and pour as much concrete as they possibly can and create facts on the ground so that Cop City is at least halfway built or most of the way built by the time any referendum actually does get in front of Atlantans.

Jay: At this point, it’s ambiguous whether it will be on a ballot this fall because of this being hung up in the courts. Is that right?

Joseph Brown: It’s not a foregone conclusion. Nothing is impossible and nothing is ever hopeless. As disillusioning as a lot of this is to look at, as much as it makes you question the workings of “democratic representative institutions,” and it’s a bipartisan thing. It’s Democrats and Republicans in Georgia thwarting the popular… As far as what anyone can tell, what the popular will is in Atlanta, it’s not to build Cop City. We don’t know what’s going to happen. There is a procedure now. There’s a really good statement by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund from back in February saying, “All right, I appreciate that you’ve laid out a process for verifying the petition signatures, but the city was proposing to use exact signature matching.” Which Democrats spent the 2020 election cycle complaining about rightly because it’s racist.

It disproportionately disenfranchises Black voters and other voters of color, and that’s the standard that Atlanta wanted to use to vet the signatures on petitions. It’s not clear what’s going to happen. Nothing is done and nothing is finished and nothing is hopeless. There’s still a lot of fight left to be done, and there is energy. I think recently a lot of the energy has been solidarity work with Gaza actually. I think a lot of the movement’s energy coalesced around the fact that Cop City would be part of this Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange program, GILEE, which I alluded to at the very beginning without saying what it was. But it’s that program that does training with counter-terrorism professionals from other countries, including Israel. And so as an intersectional movement, people take a really broad view about what are the dimensions that are converging on this site?

And one that has been really salient for a lot of people is this collaboration between Georgia law enforcement and counter-terrorism as it’s practiced on Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. So Black organizers I spoke to would say, I have solidarity with Palestinians and I know that things that are done to Palestinians are going to be done to Black people in Atlanta, and people will learn to do things to Palestinians that are currently done to Black people in Atlanta. And so there’s been a lot of combined Stop Cop City/Save Gaza protests recently on college campuses also involving tent encampments. So the movement, it changes over time ’cause the circumstances change. And I think a lot of it more recently has been interest in international solidarity struggles. And I think that also is-

Jay: You also saw that, I recall there was a real flurry of vigils and other actions internationally after police killed Tortuguita. It’s part of it, not just in US, but spread around the world, so that international solidarity part’s been present for a while. And it’s almost like you couldn’t script a case, a project that brought together more themes of social justice and activism and state responses to them than this one. It’s remarkable. You’ve touched on so many of them, that racial justice, policing, indigenous people’s rights, colonialism, writ large anarchism, abolitionism, anti-capitalism, and then how police respond to these things, how democracy is questioned or tested by these things and the international solidarity around it. It really is astonishing how all of that comes together in this one movement, this one situation.

Joseph Brown: I have a couple of thoughts in response to that. One is I’ve been talking with people post the killing of Tortuguita and post the closure of the forest and wondering what happens next. And there are so many different things converging on this site of Cop City and in this issue of Cop City, and you’re seeing this slogan pop up everywhere. I live in Boston, I’ve seen Stop Cop City graffiti in Boston and Viva Tortuguita, RIP Tort graffiti in Boston, and I didn’t put it there. In a sense, something someone told me was, “For young people right now, there is a cop city literally or figuratively in your backyard somewhere, politically speaking.” There are plans to build these kinds of facilities all over the country. There’s one in New York City that’s going to be built, maybe one proposed for Chicago, places in Michigan, Washington.

There’s also forests in need of protecting, and there’s communities in need of protecting, and there’s racialized police violence everywhere. Somewhere in your backyard as an idealistic person, maybe young, maybe not, there is a stop Cop City struggle. And it might be metaphorical, but in a way, everything good is the forest and everything bad is Cop City. And I think internationally, people see that too. It’s been very interesting to watch Tortuguita as an international symbol, and I think they’d be pleased by that as long as it’s motivating to people. It’s not great if you try and turn someone into a saint because of activism is a thing that saints do, then people who don’t feel worthy of sainthood won’t want to do activism because they won’t feel worthy of it.

And maybe to close, I think it’s important to just highlight all the ways that the person who was killed in this movement was a very ordinary person who just did the things that their conscience told them to do. They just lived out their principles. They were not an action hero. And something that they told me that isn’t in the graffiti but it’s going to be the epigraph of the book is a quote from the interview, “People don’t know the power they have until they do.” And I think that you see a movement like this that seems really special, but something near you has these elements in it too. And there are many ways to plug in, however you’re comfortable, on a lot of the same social justice, racial justice, climate, indigenous rights, all these solidarity issues. And I think that the world is full of opportunities.

Jay: Well, we could talk about this for hours. I want to be mindful of your time. One more I’d love to hear from you about, but I think that’s a good place to leave it.

Joseph Brown: Thank you very much. I really enjoyed speaking with you.

Jay: Yeah, thank you Joe. And I look forward to reading that book when you’re done with it.

Joseph Brown: Thanks. Hopefully sometime next year, it’ll be out.

Jay: Great, thanks. Take care.

Joseph Brown: You too.

Jay: Thank you for listening to the Nonviolent Action Lab podcast, hosted by me, Jay Ulfelder, and produced at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard Kennedy School. Please rate and review us wherever you listen. You can find more information about the Nonviolent Action Lab and links to our work in the show notes below.

See you next time.