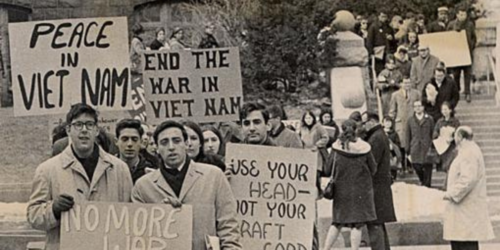

It was the fourth day of the protests—January 28, 2011. Thousands of Egyptians filled Tahrir Square and calls rang out from seemingly every corner in Cairo for a more representative government that would deliver the country out of poverty and away from corrupt rule.

It was here, as sunset began, that Shady ElGhazaly Harb’s two lives came crashing together.

ElGhazaly Harb, a surgeon by training, had long been engaged in the fight for democracy in Egypt. In 2011, as protestors swept the streets of Cairo demanding change and freedom from then-President Hosni Mubarak’s three decades of autocratic rule, he returned to Cairo after completing his fellowship at King’s College Hospital in London in order to help organize demonstrations.

Entering the square that evening, fellow protestors carried a man over to him, desperately seeking the help of a doctor. It didn’t take long for ElGhazaly Harb to pronounce the man dead from an internal hemorrhage caused by shotgun wounds.

“It was the first time that I saw one of the murders committed during the revolution,” he recalls. “It was a moment that I will never forget.”

As a protest leader, ElGhazaly Harb felt responsible and indebted to the tens of thousands of Egyptians who joined him in the square and to the millions more who joined the cascading series of protests around the Middle East and North Africa. “Many paid for the fight for freedom with their life. Which is why, even at the lowest points, I still feel that it’s my obligation to continue fighting for them,” he says.

During those tumultuous days of the Arab Spring, ElGhazaly Harb and his colleagues harnessed social media to encourage people from all walks of Egyptian society to take to the streets. The 18 days that the demonstrators controlled Tahrir Square and witnessed Mubarak’s toppling were some of the most exhilarating moments of his life. “The most beautiful days in our lives are the 18 days of the square,” he says.

But the euphoria of Mubarak’s downfall didn’t last long. Efforts to form a coalition government failed, paving the way for the Muslim Brotherhood under Mohamed Morsi to win office. Watching from the sidelines with increasing suspicion as the ill-prepared Morsi careened from one crisis to another, the military saw its chance to regain political power after popular demonstrations against the Islamist rule.

For ElGhazaly Harb, a determined advocate for a democratic Egypt, things became much more difficult. A brutal clampdown on political opposition followed, starting with the Islamists but soon spreading across the political spectrum, including secular advocates like him. When the veteran of Tahrir Square refused to stop speaking out against the quickly shrinking public space for political speech, he was imprisoned for almost two years, spending much of that time in solitary confinement.

It would be easy for him to have lost faith in his dream of a free and open government while languishing inside a prison cell, but ElGhazaly Harb refused to give the regime the satisfaction of walking away from what he saw as his life’s work. Instead, he saw his time in prison as merely the next stage in his ongoing fight for Egyptian democracy. Even while incarcerated, he staged a hunger protest as another way to speak out.

Released from prison in March 2020, a fellow activist suggested that he apply to the Kennedy School to learn new insights and strategies to advance his struggle for democracy. This past year, ElGhazaly Harb enrolled at HKS as a Mid-Career Master in Public Administration student and was awarded a Ford Foundation Mason Scholarship by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

At the Kennedy School, ElGhazaly Harb found new expertise both inside and outside of the classroom. “A lot of professors have inspired me,” he says. “All these people, with this amount of knowledge and experience with governance and democracy, reading their books is one thing, but interacting with them is different.”

He credits the Ford Foundation Professor of Democracy and Governance Tarek Masoud, faculty director of the Kennedy School’s Middle East Initiative and the Ash Center’s Initiative on Democracy in Hard Places, with guiding him through the Kennedy School and helping him select courses that would build on his work as a civil society actor. “At a time when many in the West are expressing misgivings about democracy and a willingness to entertain alternative forms of government in the name of efficiency, Shady’s strong normative commitment to democracy, and to fighting for it on behalf of Egyptians and all the peoples of the Middle East is nothing short of inspiring to me,” Masoud says. “Shady has testified to how much he’s learned at the Kennedy School, but in my case, at least, the learning has gone both ways.”

And when it comes to courses, it’s hard for ElGhazaly Harb to highlight just one. “The Kennedy School has given me a lot,” he says, citing lectures by faculty including Erica Chenoweth, Ricardo Hausman, Ron Heifetz, Marshall Ganz, and Dan Levy.

With the opportunity in the classroom to revisit the revolution and explore new perspectives on democratic reforms, ElGhazaly Harb has been able to develop a broader understanding of the factors that have led to a return of authoritarian rule in Egypt – and what may ultimately lead to its downfall. These insights come at an opportune time as the Egyptian economy continues to struggle, and momentum for change is again building. “I anticipate that sooner or later Egypt will change, and when that happens, we need to be better prepared,” he says. “After learning all the difficult lessons we’ve been through, I think this change can take us to a much better place.”

As he prepares to graduate, ElGhazaly Harb is imbued with a continued sense of hope for what can be accomplished not only in Egypt but beyond its borders as well. “Egypt is the cultural and political epicenter of the region, and whenever something happens there, it will reverberate all over. If we manage to bring about a sustained democratic transition in a gradual manner that will not slide it into chaos, we will be setting an example in a very strategic region of the world,” he says. “I’m not just hopeful about Egypt, but I’m hopeful about the whole region.”