Podcast

So, Is It Fascism?

Jonathan Rauch joins the podcast to discuss why he now believes “fascism” accurately describes Trump’s governing style.

Commentary

In this paper, Mary W. Graham, co-director of the Center’s Transparency Policy Project, explores the unintended information inequities that weaken the nation’s vital health and safety alerts. By examining three policies — wildfire alerts, drinking water reports, and auto safety recalls — she suggests common sources of inequality problems and steps policy makers are taking to remedy them.

Six years ago, when California’s deadliest wildfire killed 85 people in the town of Paradise, more than three-quarters of those who died were 65 or older or had disabilities. Many never received evacuation alerts.1 More recently, 93 percent of those who died in the tragic January 2025 Eaton and Palisades fires were 65 or older or had disabilities, according to the Los Angeles County medical examiner’s preliminary report.2 When Flint, Michigan’s drinking water became dangerously contaminated for 18 months in 2014 and 2015, those with modest incomes or limited English were more likely than others to be exposed to water infused with harmful chemicals without their knowledge. In a critical auto safety alert, owners with less education, lower income, or less English proficiency were less likely to hear about the recall. Many used car owners were also left out of required alerts. These crises reveal a surprising fact: The nation’s vital health and safety alerts intended to reach all Americans sometimes have built-in information inequities with deadly consequences.

That was never the intention. Elected officials have long required that all members of the public be informed about hidden risks in everyday life. When markets do not provide the information people need to make informed choices about their health and safety, legislators add disclosure requirements. Federal laws require employers to report workplace safety hazards, manufacturers to disclose toxic chemical releases, and food companies to recall contaminated products. For wildfires, California law calls for counties to plan for the evacuation of older residents and those with disabilities.3 Such transparency policies are often supported by lawmakers across the political spectrum because they promote informed choice while respecting Americans’ varied preferences and companies’ varied capabilities.

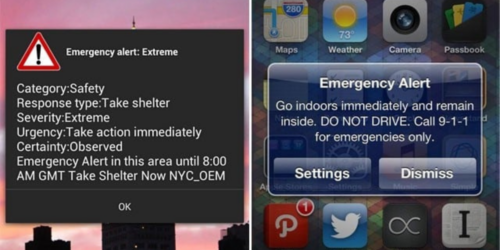

But in practice, information may not get to all Americans when and where they can access, understand, and act on it to protect themselves and their families. Ironically, advances in communication technology have added new dimensions to an old problem. As people use a wider variety of communication channels, it becomes harder to reach everyone. And as communities transition to cell phone and email alerts, those without access are often left behind. Accurate and timely information alone does not assure health and safety, of course. But informed choice provides the essential first step. In debates about many aspects of inequality in the United States, such information inequities have received little attention. Yet they can be a matter of life or death.

Wildfire alerts, drinking water contamination warnings, and auto safety recalls are among the nation’s enduring commitments to inform all Americans about hidden risks. A closer look at how they have served the public provides clues about the causes of information inequities and their remedies.

The Camp Fire (named after Camp Creek Road where it started) killed more than 85 people and destroyed nearly all the homes in Paradise, California.4 When fire broke out on November 8, 2018, alerts left many older residents uninformed and unprepared. Seventy-seven percent of those who died in the Camp Fire were 65 years or older or had disabilities.5

Paradise’s risk of fire was well-known. Days before the fire, a national rating system had ranked Butte County’s fire risk as very high due to winds and drought, and the state’s regional forecasting service issued a red flag warning for the county on November 6.

A year earlier, the town had contracted with a private company, OnSolve, to provide wildfire alerts via cell phone, text, and email. But its CodeRED software system required residents to sign up to receive the warnings. Only about a third did. This “opt-in” system was especially ineffective for older residents, many of whom did not have cell phones or lived where internet service was unreliable. A county special needs program to prioritize the evacuation of residents who were older or had disabilities also required sign-up and was not tied into evacuation plans.6 As a result, there were two kinds of information problems: Officials did not know where those in need were located, and those in need did not know about the danger or how to seek help. The county district attorney’s investigation that documented each fatality concluded that many older residents were found still inside their homes, some near their walkers or wheelchairs.7

Older residents might have relied on the 911 system for aid and instructions. But 911 also failed. One or two dispatchers were on duty as the fire spread, but they were swamped with hundreds of calls from residents as wind-swept embers rained down on the town. Soon all landline calls failed as the fire burned through the area’s above-ground cables. Since the town had no sirens, first responders resorted to low-tech warnings—knocking on doors and driving through neighborhoods with loudspeakers.

National data confirms that older residents face special problems receiving, understanding, and acting on disaster alerts. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reports that older adults face the greatest relative risk of dying in a fire, with the wildfire death rate per million for those 65 and over increasing by 23 percent from 2013 to 2022. In 2022, the relative risk of dying in a fire for older adults was 2.6 times higher than that of the general population.8 W. Craig Fugate, administrator of FEMA from 2009 to 2017, counted the failure to plan the protection of vulnerable people among the “seven deadly sins” of emergency management.9

“We have to fundamentally change our approach to emergency management,” said L. Vance Taylor, chief of the Office of Access and Functional Needs in the California governor’s Office of Emergency Services, in a 2019 interview with Laura Newberry of the Los Angeles Times. “Vulnerable residents must be sought out before, during, and after disasters.”10

The many failures that contributed to 18 months of dangerous contamination of Flint, Michigan’s drinking water with lead, harmful bacteria, and chlorine byproducts in 2014 and 2015 disproportionately threatened the health of low-income residents and those who were not proficient in English. Michigan Governor Rick Snyder later testified before a House committee that “this was a failure of government at all levels.”11

In April 2014, Flint, Michigan, began drawing drinking water from the Flint River while a new pipeline from Lake Huron was being built. Flint, a city of nearly 100,000 residents, of whom more than 40 percent were low income, was governed at the time by a state-appointed emergency manager due to chronic budget deficits. The new pipeline would save money, but it was also well-known that the chemical and bacterial content of the river water varied by temperature, season, and flow. In addition, some parts of the city had old lead service pipes that could leach lead into drinking water, a fact that residents were often unaware of. The city did not add corrosion control to the river water to prevent leaching, and there was some confusion among state and local officials about whether such control was required. (It was.) For children, exposure to any amount of lead could interfere with growth and development.

Residents noticed immediately that the river water tasted and smelled bad and was sometimes yellow or brown in color. Soon some reported skin rashes, hair loss, and other unusual symptoms. State and local officials continued to maintain that the water was generally safe to drink but also issued several time-limited “boil water” alerts due to bacterial contamination.12

When officials did not respond to their complaints, many concerned residents searched the internet for information. One created a Facebook page where residents could post concerns and plan action. Citizen groups organized meetings to share information and protest the water quality. In October, the local General Motors (GM) plant stopped using city water due to concerns about corrosion of its equipment.13

Early in 2015, some residents reported more health problems, including muscle aches, weight loss, and stomach trouble. Local regulators admitted that the water had violated federal standards for chlorine by-products during three earlier months. Without informing the public, the state began providing bottled water to its own employees in its Flint office building.

Finally, a year and a half after the city began drawing drinking water from the river, an experienced researcher from Virginia Polytechnic Institute contacted by local residents enlisted students and local volunteers to conduct broader sampling. He found elevated lead levels in 40 percent of more than 250 samples.14 In October 2015 the city finally discontinued its use of river water, contracting instead with Detroit’s water authority to provide water from Lake Huron.

Information failures left vulnerable residents at greater risk. Those who lived in older homes or apartments were more likely to have corroding lead service lines without knowing about the risk, and a local pediatrician reported higher levels of lead in the blood of children from impoverished neighborhoods.15 A governor’s taskforce reported in 2016 that residents who were not proficient in English were often left out of communications: “For non-English-speaking Flint residents, [t]he sight of uniformed state troopers and National Guardsmen entering neighborhoods in convoys with flashing lights frightened many who did not open their doors. . . . Initial requirements for identification scared many families.”16

In the absence of government information, those whose communication habits did not include receiving online information from community groups were at a disadvantage. Only about half of the city’s residents had home internet connections, and families did not know that children at three elementary schools were in danger from lead in school water that tested as much as six times the federal limit. Information that spread by word of mouth failed to reach those less connected. Officials did not tell residents that the state provided its employees with free bottled water or that GM’s employees gained access to cleaner Lake Huron water when the plant stopped using city water.

Inequities are also built into the national reporting system for drinking water contamination. Digital technology now makes it possible for water authorities to track contaminants in near real time, but Americans with special health vulnerabilities remain uninformed. An outdated federal law requires notice of contaminants to customers only once a year, despite pollution fluctuations. (A new rule requires large systems to report twice a year beginning in 2027 and to make reports more readable.17) Otherwise, water authorities alert customers only when pollution exceeds national standards. But those standards do not reflect the varying health needs of young children, older people, pregnant women, or those with compromised immune systems, and they often lag behind advancing science.18 With today’s technology, water authorities could provide the public with current information about contaminants as soon as they receive results and check them for accuracy. Better information could increase the public’s confidence, as Americans do not trust their drinking water. In 2024, a Gallup poll found that 82 percent of those surveyed worried a fair amount or a great deal about drinking water contamination, their biggest environmental concern.19

A review of the two most serious safety recalls of recent years reveals that owners with limited financial resources, limited English, or who buy used cars are less likely to receive alerts and get their cars repaired.

Recognizing that some safety problems become apparent only after new cars are on the road, federal law has required since 1966 that auto manufacturers disclose defects and provide repairs. It has long been illegal to sell a new car in the United States with an unrepaired safety defect. The government’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) is responsible for overseeing safety recalls of millions of cars each year. In 2023, for example, it recalled more than 30 million vehicles to fix safety problems.20

Press reports suggest that as early as 2001, some GM employees were aware that faulty ignition switches, mainly in its Chevy Cobalt and Saturn Ion cars, sometimes shut off the cars’ electrical systems without warning, stopping the engine, preventing airbags from deploying, and sometimes leading to serious accidents.21 After the death of a young Maryland driver in 2005, in a routine service bulletin to dealers, GM suggested that they tell buyers not to add items to their key chain. The idea was that added weight could trigger the defective switch.22 Two years later, federal safety officials recommended an investigation of 29 complaints and 4 fatal accidents. But it was not until 2013 that GM finally acknowledged that the faulty ignition switch had so far caused 31 crashes and 13 deaths.23 In March 2014, GM’s new leader, Mary Barra, apologized for the company’s mishandling of the defect. However, by 2024, 124 deaths had been attributed to the faulty switch,24 and the company had recalled more than 16 million25 vehicles and paid out more than $2 billion in fines and settlements.26

As evidence of GM’s ignition switch defect was emerging, another serious safety problem developed involving many more cars. It became the nation’s largest and most complex auto recall ever. Several auto companies used airbags made by Japanese supplier Takata Corporation in the early 2000s as a cost-cutting measure. Later evidence, according to New York Times reporting, indicated that some Takata employees may have known as early as 2001 that the airbags could be faulty.27 In 2008 Honda began recalls to repair the defect, followed by four other manufacturers in 2013.28 By 2024, 19 different manufacturers had recalled over 42 million vehicles to replace 67 million airbags made by Takata.29 The exploding propellant was linked to 28 deaths and more than 400 injuries.30 Manufacturers issued “do not drive” orders for cars most at risk, and unprecedented efforts to reach owners and encourage repairs led to the replacement of 88 percent of airbags.31 Nonetheless, according to CARFAX, more than six million cars with defective airbags remained on the road in 2024.32

The numerous obstacles to effective alerts and repairs for owners with limited financial resources, language limitations, or used cars start with information problems. Manufacturers must repair safety defects in new cars without charge to the owner. But an outdated federal law requires that manufacturers notify owners of safety recalls by first-class mail. These mailed notices often never reach second or third owners whose addresses are unknown to dealers, and purchasers with language limitations may not understand the notices, their urgency, or how to navigate the sometimes-complex repair process. Manufacturers are not required to inform used car owners of alerts unless the owners are registered with the state, and federal law does not require used car sellers to inform owners or complete safety repairs before a sale.

In a 2024 report, Congress’ General Accountability Office (GAO) found evidence that owners with less education, lower income, or less English proficiency were less likely to hear about recalls or get their cars repaired. Its review of research found that transient or lower-income owners were less likely to list a current mailing address with dealers or a state motor vehicle department (DMV) and that misunderstanding about the cost of repairs remained a significant barrier for them.33 By contrast, NHTSA research suggested that owners with newer cars, with continuing contacts with a dealer, and with the language and education skills to understand risks were more likely to receive alerts and get their cars repaired. NHTSA’s “tips” to manufacturers advised use of plain language, clarity about urgency, and adoption of multiple approaches to reach owners, including certified mail, emails, texts, non-English media, advertisements, and community events.34

***

These cases suggest that the national commitment to inform the public about hidden risks in daily life can remain a hollow promise for vulnerable Americans. When lives are at stake, well-intentioned policies intended to provide critical health and safety information to everyone often fail to reach people who are older, disabled, low income, or not adept in English. Marketing specialists and politicians have mastered the art of customizing information to reach diverse customers or voters when and where those individuals like to receive it. But public risk communication has not kept pace. Technology-based evacuation alerts do not reach many older residents, auto safety recall notices do not reach owners of used cars, and water customers with special health needs do not receive timely reports of pollution that may harm their health.

Ironically, completing this “last mile” of information to reach those at risk is becoming more difficult as technology fragments communication. Americans no longer rely on common news sources. For example, a 2024 Pew/Knight poll found that three-quarters of community residents sometimes or often get local news from family and friends, two-thirds at least sometimes rely on television news, half turn to radio or online sources, and more than a third rely on churches or other local organizations. Only about a third rely on information coming directly from local government.35

However, there are also early signs that public officials are grappling with the issue. In 2024, California state guidelines called for communities to pay special attention to wildfire warnings for those with disabilities, language issues, limited income, or lacking transportation. They noted that it is “imperative for jurisdictions to understand that individuals with access and functional needs are often at greater risk for negative outcomes associated with disasters and may require additional time and resources to act on alert and warnings messages.”36 In April 2025 the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to require officials to consider creating a registry of vulnerable individuals who might need help in emergencies. Additionally, the 2021 federal Infrastructure Act created a grant program to assist communities and tribes in reducing wildfire risk, prioritizing low-income or underserved communities. Researchers are also beginning to assess the increased risks of wildfires to vulnerable Americans37 and suggest customized approaches to assist them.38 Smart sirens provide one way of reducing inequities by combining advancing technology with traditional warnings that reach nearly everyone. Paradise, California, installed 21 smart sirens in 2023 that emit one-minute two-tone alarms followed by voice evacuation instructions. The town also buried cables underground to preserve power and communication during fires.39

Auto manufacturers’ and dealers’ responses to the Takata airbag defect included unprecedented efforts to reach owners by certified mail, postcard, email, phone calls, social media in English and Spanish, and personal house calls as lawsuits mounted.40 Some dealers also offered free loaner cars, shuttle services, towing, and mobile repairs at owners’ homes or businesses. Manufacturers worked with DMVs, car repair shops, insurers, and the National Safety Council to encourage owners in underserved communities to get repairs. Three states used federal grants to tie recall notices to car registration renewals or annual safety inspections, and in 2017, Tennessee passed a law aimed at closing the “used car loophole” by requiring used car dealers to either complete recall repairs before a sale or inform buyers about recalls.41 Additionally, pressed by Congress in 2015 and 2021 legislation to better inform owners, manufacturers continued to experiment with new communication strategies to reach affected owners.

Most presidents since the 1970s have issued executive orders urging agencies to keep federal rules current as circumstances change and to monitor their effectiveness.42 Nonetheless, critical health and safety alerts leave behind millions of Americans who do not receive or understand information about threats. To fulfill the promise of an informed public, public officials will need the political will to require fair and effective communication.

Mary W. Graham co-directs the Transparency Policy Project at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. Her research focuses on the politics of public information. Elisabeth B. Silva led the research for this article.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily represent the positions of the Ash Center or its affiliates.

LA Times/Maria L. La Ganga et al., “Many victims of California’s worst wildfire were elderly and died in or near their homes, new data show”, https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-paradise-fire-dead-map-20181213-story.html, 12/13/2018

LA Times/Laura Newberry, “Poor, elderly and too frail to escape: Paradise fire killed the most vulnerable residents”, https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-camp-fire-seniors-mobile-home-deaths-20190209-story.html, 02/10/2019

CalFire/Incidents, “Camp Fire”, https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2018/11/8/camp-fire

California Legislative Information, Assembly Bill 2311, Chapter 520, Signed by Governor September 23, 2016, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160AB2311

NIH/National Library of Medicine/Arash Modaresi Rad et al., “Social vulnerability of the people exposed to wildfires in U.S. West Coast states”, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10511185/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20people%20exposed,in%20California%20(~8%25)

Cal. Governor’s Office of Emergency Services/Dir. Nancy Ward, “State of California Alert & Warning Guidelines”, https://www.caloes.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/Preparedness/Documents/Statewide_Alert_and_Warning_Guidelines_May_2024.pdf, May 2024

Butte County District Attorney/Michael L. Ramsey, “The Camp Fire Public Report: A Summary of the Camp Fire Investigation”, https://www.buttecounty.net/DocumentCenter/View/1881/Camp-Fire-Public-Report—Summary-of-the-Camp-Fire-Investigation-PDF, 06/16/2020

Butte County, “Special Needs Awareness Program”, https://www.buttecounty.net/1790/Special-Needs-Awareness-Program

FEMA/U.S. Fire Administration, “Older Adult Fire Death Rates and Relative Risk (2013-2022),

https://www.usfa.fema.gov/statistics/deaths-injuries/older-adults.html

AP News/Olga Rodriguez and Haven Daley, “California town of Paradise deploys warning sirens as 5-year anniversary of deadly fire approaches”, https://apnews.com/article/paradise-camp-wildfire-warning-sirens-b4f6a50f7dc5bf1ab4b6f517df2662df, 08/17/2023

Everbridge/Soraya Sutherlin, “Lessons Learned from the California 2020 Wildfire Season”, https://go.everbridge.com/rs/004-QSK-624/images/Everbridge%20Lessons%20Learned%20from%20the%20California%202020%20Wildfire%20Season%20White%20Paper%20Final%20Copy.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1aADGP8RquUCdiK2RlWZ1KFPwtapUIp7fJ2GJV9h2osIOzjqlr9_Tlmyo

AP News/Jocelyn Gecker and Janey Har, “Paradise area was a heaven for victims of deadly wildfire”, https://apnews.com/article/fires-north-america-us-news-ap-top-news-paradise-b49c4dbdaa544427930637926f16fb42, 02/15/19

The Guardian/Alastair Gee and Dani Anguiano, “Last Day in Paradise: The Untold Story of How a Fire Swallowed a Town”, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/dec/20/last-day-in-paradise-california-deadliest-fire-untold-story-survivors#:~:text=6%20years%20old-,Last%20day%20in%20Paradise%3A%20the%20untold%20story%20of,a%20fire%20swallowed%20a%20town&text=William%20Goggia%20awoke%20to%20a,tanks%20exploding%20in%20the%20distance, 12/20/2018

National Institute of Standards and Technology, Technical Note NIST TN 2105/Alexander Maranghides et al., “Camp Fire Preliminary Reconnaissance”, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/TechnicalNotes/NIST.TN.2105.pdf, August 2020

National Institute of Standards and Technology, Technical Note, NIST TN 2252/Alexander Maranghides et al, “A Case Study of the Camp Fire: Notification, Evacuation, Traffic, and Temporary Refuge Areas (NETTRA)”, Part 6. p. 41, Emergency Notifications, and Appendix D. CodeRED Statistics, https://www.nist.gov/publications/case-study-camp-fire-notification-evacuation-traffic-and-temporary-refuge-areas-nettra, 07/18/2023

PBS Frontline/Zoe Todd, Sydney Trattner, Jane McMullen, Ahead of Camp Fire Anniversary, New Details Emerge of Troubled Evacuation, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/camp-fire-anniversary-new-details-troubled-evacuation/, 10/25/2019

Tribune News Service/Lisa Krieger, “Camp Fire Aftermath: ‘Technology, the Thing I Trust Most, Failed’”, https://insider.govtech.com/california/news/camp-fire-aftermath-technology-the-thing-i-trust-most-failed.html, 12/16/18

Daily Democrat/Bay Area News Group/Lisa Krieger, “Wildfire alert system failed”, https://www.dailydemocrat.com/2018/12/16/wildfire-alert-system-stumbled/, 12/18/2018

U.S. Department of Commerce/National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/National Weather Service Western Region Headquarters/Jeffrey Zimmerman, Acting Director, Western Region, Service Assessment “November 2018 Camp Fire”, https://www.weather.gov/media/publications/assessments/sa1162SignedReport.pdf, January 2020

NBC News/James Rainey, “Paradise Fire survivors say warnings were too little, too late”, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/paradise-fire-survivors-say-warnings-were-too-little-too-late-n935846, 11/14/2018

LA Times/Paige St. John, Joseph Serna, and Rong-Gong Lin II, “Here’s how Paradise ignored warnings and became a deathtrap”, https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-camp-fire-deathtrap-20181230-story.html#:~:text=A%20large%20portion%20of%20Paradise,were%20sent%20to%20three%20others., 12/30/2018

capradio/NPR: Cal State U./Bob Moffitt, “Many Residents Did Not Receive Emergency Alerts During The Camp Fire. Will You Be Warned If A Disaster Is Heading Your Way?”, https://www.capradio.org/articles/2019/07/11/emergency-alert-will-you-be-notified-if-a-wildfire-is-heading-toward-your-town/, 07/11/2019

YouTube/ASPO Sverige (W. Craig Fugate), “The 7 Deadly Sins of Emergency Management” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iRWfDFM19e8

ScienceAdvances/Arash Modaresi Rad et al., “Social vulnerability of the people exposed to wildfires in U.S. West Coast states”, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adh4615

ScienceDirect/Yuran Sun et al., “Social vulnerabilities and wildfire evacuations: A case study of the 2019 Kincade fire, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925753524001474?ref=pdf_download&fr=RR-2&rr=91cab52bde1ae5b2

FireRescue1.com/Rebecca Ellis – LA Times, “Calif. wildfires lead officials to consider evacuation database for the disabled”, https://www.firerescue1.com/emergency-management/calif-wildfires-lead-officials-to-consider-evacuation-database-for-the-disabled, January 26, 2025

ProPublica/Agnel Philip, “The EPA Has Found More Than a Dozen Contaminants in Drinking Water but Hasn’t Set Safety Limits on Them”, https://www.propublica.org/article/epa-safe-drinking-water-act-contaminants-regulation, 11/6/2023

Gallup/Mary Claire Evans, “Seven Key Findings About the Environment on Earth Day”, https://news.gallup.com/poll/643850/seven-key-gallup-findings-environment-earth-day.aspx, 04/22/2024

NPR/Laura Wagner and Merrit Kennedy, “Michigan Governor Rick Snyder: ‘We All Failed the Families of Flint’”https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/03/17/470792212/watch-michigan-gov-rick-snyder-testifies-on-the-flint-water-crisis, 03/17/2016

NPR/Merrit Kennedy, “Lead-Laced Water in Flint: A Step-By-Step Look at the Makings of a Crisis”, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/04/20/465545378/lead-laced-water-in-flint-a-step-by-step-look-at-the-makings-of-a-crisis, 04/20/2016

Water Alternatives (Journal), Volume 15, Issue 3/Melissa Heil, Illinois State University, “Barriers to Accessing Emergency Water Infrastructure: Lessons from Flint, Michigan” https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol15/v15issue3/677-a15-3-6/file

Flint Water Advisory Task Force Final Report/Chris Kolb and Ken Sikkema co-chairs, https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/formergovernors/Folder6/FWATF_FINAL_REPORT_21March2016.pdf?rev=284b9e42c7c840019109eb73aaeedb68, March 2016

“A Closer Look at the Demographics of Flint, Michigan”, https://apnews.com/general-news-7b2bcfdcc8d74ece9e0cb167a2239745:, 01/21/2016

Harvard Kennedy School Case 2237.0/Pamela Varley and Christopher Robichaud, “The Making of a Public Health Catastrophe: A Step-By-Step Guide to the Flint Water Crisis”, https://www.thecasecentre.org/products/view?id=184445, 01/19/2022

Detroit Free Press/Paul Egan, “Flint Red Flag: 2015 Report Urged Corrosion Control”, https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/flint-water-crisis/2016/01/21/flint-red-flag-2015-report-urged-corrosion-control/79119240/, 01/21/2016

Harvard Kennedy School Shorenstein Center/Derrick Z. Jackson, “Environmental Justice? Unjust Coverage of the Flint Water Crisis”, https://shorensteincenter.org/environmental-justice-unjust-coverage-of-the-flint-water-crisis/, 07/11/2017

ABC News/Caresse Jackson, “Flint Switches Back to Detroit Water System”, https://www.abc12.com/news/flint-water-emergency/flint-switches-back-to-detroit-water-system/article_44e64bc3-51e8-5a07-b4e7-4494876e12bf.html, 10/16/2015

New Jersey Division of Water Supply & Geoscience, “NJ Drinking Water Watch”, https://www-dep.nj.gov/DEP_WaterWatch_public/

Deadly Auto Defects

Carfax.com/Patrick Olsen, “Takata Airbag Recall: 6.4M Cars Still Need Replacements in 2024” https://www.carfax.com/blog/takata-airbag-recall#:~:text=Ten%20years%20after%20the%20National,airbags%2C%20according%20to%20CARFAX%20data, 05/29/2024

NHTSA, https://www.trafficsafetymarketing.gov/sites/tsm.gov/files/2024-08/vehicle-recalls-exploratory-research-en-2024-16357-v1-tag.pdf, 05/16/2024

Pew Research Center/Elisa Shearer, “Friends, family and neighbors are Americans’ most common source of local news”, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/09/26/friends-family-and-neighbors-are-americans-most-common-source-of-local-news/, 09/26/2024

New York Times/Danielle Ivory, “G.M’s Ignition Problem: Who Knew What When”, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/05/18/business/gms-ignition-problem-who-knew-what-when.html, 09/15/2014

NPR/Tanya Basu, “Timeline: A History of GM’s Ignition Switch Defect”, https://www.npr.org/2014/03/31/297158876/timeline-a-history-of-gms-ignition-switch-defect, 03/31/2014

The Detroit News/David Shepardson, “GM Compensation Fund Completes Review with 124 Deaths”, https://www.detroitnews.com/story/business/autos/general-motors/2015/08/24/gm-ignition-fund-completes-review/32287697/, 08/24/2015

New York Times/Neal E. Boudette, “Supreme Court Rebuffs G.M.’s Bid to limit Ignition-Switch Lawsuits”, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/24/business/supreme-court-general-motors-ignition-flaw-suits.html, 04/24/2017

New York Times/Hiroko Tabuchi, “A Cheaper Airbag, and Takata’s Road to a Deadly Crisis”, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/27/business/takata-airbag-recall-crisis.html, 08/26/2016

U.S. Department of Transportation/NHTSA/Frank Borris, “Supplemental Statement for the Record: NHTSA’s Historical Timeline of Events Regarding Takata Inflator Ruptures”, https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/documents/nhtsa_historical_timeline_takata_inflators.pdf, 10/22/2015

Consumer Reports, “Takata Airbag Recall: Everything You Need to Know” https://www.consumerreports.org/cars/car-recalls-defects/takata-airbag-recall-everything-you-need-to-know-a1060713669/, 08/13/2024

NHTSA “2023 Annual Report, Safety Recalls”, https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/2024-03/NHTSA-2023-Annual-Recalls-Report_0.pdf, March 2024

GAO/Elizabeth Repko, “Report to Congressional Committees/Vehicle Safety/Opportunities to Improve Repair Rates for Recalled Vehicles”, https://www.gao.gov/assets/d24106356.pdf, January 2024

Federal Register, “Update Means of Providing Recall Notification”, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/01/2016-20926/update-means-of-providing-recall-notification, 9/1/2016

Wall Street Journal/Andrea Fuller and Adrienne Roberts, “Car Makers’ Struggles With Recalls Leave More Risky Vehicles on the Road”, https://www.wsj.com/articles/on-some-big-recalls-car-companies-make-little-headway-1541070000, 11/01/2018

New York Times/Christopher Jensen, “Buyer Beware: ‘Certified’ Used Cars May Still Be Under Recall”, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/16/business/buyer-beware-certified-used-cars-under-recall.html, 12/16/2016

Alliance for Automotive Innovation, ”Recall Awareness” https://www.autosinnovate.org/recalls

Congressional Research Service/Bill Canis, “Motor Vehicle Safety: Issues for Congress/The 2015 FAST Act and Unresolved Issues/Major Safety Provisions” (p.16) https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46398/6, 7/24/2020

U.S. Code of Federal Regulations/Subtitle B, Chapter V, Part 577 “Defect and Noncompliance Notification”, Paragraph 577.7 “Time and manner of notification”, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/subtitle-B/chapter-V/part-577, [41 FR 56816 preview citation details, Dec. 30, 1976, as amended at 60 FR 17271, Apr. 5, 1995; 69 FR 34959, June 23, 2004; 70 FR 38814, July 6, 2005; 78 FR 51422, Aug. 20, 2013; 79 FR 43678, July 28, 2014]

NHTSA, “Tips for Increasing Recall and Completion Rates”, https://www.nhtsa.gov/vehicle-manufacturers/tips-increasing-recall-completion-rates

National Archives and Records Administration/Federal Register, “Executive Order 13563, Section 6”, https://www.federalregister.gov/reader-aids/office-of-the-federal-register-announcements/2011/02/executive-order-13563-and-incorporation-by-reference#:~:text=Section%206%20of%20Executive%20Order,so%20as%20to%20make%20the

NHTSA, “Takata Recall Spotlight”, https://www.nhtsa.gov/vehicle-safety/takata-recall-spotlight#:~:text=NHTSA%20has%20confirmed%20that%2028,exploding%20Takata%20air%20bag%20inflators.

Executive Order 13563, Section 6, https://www.federalregister.gov/reader-aids/office-of-the-federal-register-announcements/2011/02/executive-order-13563-and-incorporation-by-reference#:~:text=Section%206%20of%20Executive%20Order,so%20as%20to%20make%20the

Podcast

Jonathan Rauch joins the podcast to discuss why he now believes “fascism” accurately describes Trump’s governing style.

Podcast

Drawing on new data from more than 10,000 Trump voters, this episode of Terms of Engagement unpacks the diverse constituencies behind the MAGA label.

Podcast

As Venezuela grapples with authoritarian collapse and a controversial U.S. operation that removed Nicolás Maduro, Freddy Guevara joins the podcast to discuss what Venezuelans are feeling and what democratic renewal might actually look like.