Commentary

How Maduro’s Dictatorship Plans to Survive

Even with Nicolás Maduro gone, the fight for Venezuela’s future is far from over. Freddy Guevara warns that Maduro’s successors are more interested in regime survival than democratic reform.

Commentary

Matthew Cebul and Sharan Grewal explain that dictators around the world have been emboldened by the Trump administration’s abandonment of democracy and human rights norms, but crackdowns may spark stronger and more unified pro-democracy movements.

In his second term, U.S. President Donald Trump is aggressively undermining global norms of democracy and human rights. In his first 100 days, Trump has eliminated billions of dollars in foreign assistance and democracy aid; withdrawn support for democratic Ukraine in its fight against Russian aggression; praised El Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele for his draconian repression; and watered down the State Department’s annual human rights reports, part of a broader department pivot away from human rights as a policy priority. And at home, the Trump administration is abducting and seeking to deport foreign students for constitutionally protected speech, and disappearing immigrants in violation of basic due process.

These actions paint an unmistakable picture: Trump is disinterested in, if not openly hostile to, liberal democratic norms. To be sure, the United States’ past commitment to democracy promotion was far from absolute. Yet Trump has quashed any sense that democracy and human rights are meaningful priorities for U.S. foreign policy.

The effects of global norms can be difficult to quantify. Yet there is already reason to believe that diminished American support for democratic values is facilitating an uptick in global repression. Last month, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan arrested Ekrem İmamoğlu, mayor of Istanbul and the opposition’s main presidential candidate, and attempted to ban the protests that followed. Many believe that Erdoğan was willing to take such brazen action because he knew the Trump administration would do little in response. It took over a week for Secretary of State Marco Rubio to comment on the arrest, and notably, he expressed more concern about instability and civic unrest than about İmamoğlu’s unjust detention. Rubio then pledged to “restart” the “very good working relationship with Erdogan” from the first Trump administration. The message was clear: the United States would let repression slide.

If İmamoğlu’s arrest was a watershed moment, the floodwaters are now pouring in. Several dictators have attempted to follow Erdoğan’s lead. In Tanzania, the main opposition leader, Tundu Lissu, was arrested on April 9 on charges of treason after calling for electoral reform, with his party, Chadema, subsequently banned outright from this year’s elections. In Tunisia, a mass trial on April 19 sentenced 40 opposition figures to between 13 and 66 years in prison on fictitious charges of conspiring against the state, the most severe crackdown on the opposition since President Kais Saied’s power grab in 2021. And in Jordan, the government last week moved to outlaw the largest opposition movement, the Muslim Brotherhood, on charges of plotting attacks.

In other cases, dictators have explicitly cited Trump’s illiberalism to justify human rights crackdowns. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s government has banned the annual Pride parade, noting that the “American boot” had now been lifted. “The world has changed,” Orbán explained, “it’s clear [Pride] won’t have international protection” anymore. Similarly, in Serbia and Georgia, governments have invoked the Trump administration’s claims of fraud in pro-democracy U.S. Agency for International Development funding to constrict civil society groups there, crossing red lines that they had previously respected.

It is hard not to read these many examples as suggesting that the Trump administration is enabling, if not emboldening, repression abroad. Reassured that U.S. support will continue, autocrats feel they now have free rein to curtail dissent. After all, if the United States is shredding democratic norms at home, surely they can get away with it, too.

That said, worsening global repression will not go uncontested. Even if international pressure for human rights dissipates, repression still carries important domestic costs. Repression deepens popular grievances and erodes illiberal rulers’ facade of democratic legitimacy. Major crackdowns may also provide focal points that unite the opposition and increase mass protest, which scholars call the “backlash” or “backfire” effect.

In other words, oppressive rulers attempting to exploit a more permissive international environment may wind up with more domestic dissent than they bargained for, not less. And indeed, there is abundant evidence that people are mobilizing in response to civil liberty restrictions in their countries. İmamoğlu’s arrest sparked enormous protests against Erdoğan, larger even than the 2013 Gezi Park protests. In Georgia, Serbia, and Hungary, democratic backsliding has likewise been accompanied by strengthened pro-democracy protests. Although overwhelming repression does sometimes stifle dissent (e.g., Hong Kong), this backlash pattern is borne out in many other recent cases, from Guatemala to Senegal and South Korea. In short, while the United States under Trump may not foster democratic values abroad, everyday citizens are consistently mobilizing against authoritarian overreach.

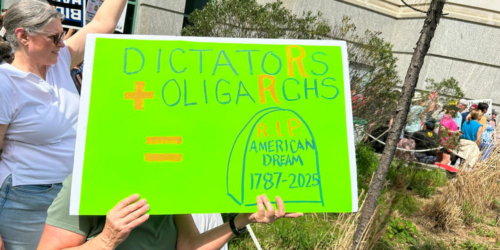

Moreover, at home, the United States is likewise witnessing a growing pro-democracy movement. Though there has not yet been a single-city protest as large as the 2017 Women’s March, protests have already reached historic levels nationwide, with millions of Americans participating in the April 5 “Hands Off” protests. The mounting domestic resistance to Trump suggests a second important caveat: the United States’ retreat from liberalism is not set in stone. Trump is already historically unpopular, as Americans recoil against tariff-induced economic instability and Trump’s overreaching of executive powers. As Trump’s popularity fades, the permissive or emboldening effects of his rule abroad may weaken. 2028 U.S. presidential contenders may look to move past a term-limited Trump, disavowing his worst impulses and potentially righting the pro-democracy axis of U.S. foreign policy. And the world’s autocrats may reconsider the risk of retroactive sanction for gross abuses—as with Bukele, who Democrats are already warning about the consequences of continued cooperation with Trump’s unlawful imprisonment schemes.

In sum, global politics under the second Trump presidency will likely be highly contentious, with both worsening repression and increased popular protest. Autocrats may seek to exploit a weakening global rights regime. Yet in so doing, they may instead give rise to stronger, more unified pro-democracy movements that ultimately provide the foundation on which to revitalize liberal democratic norms in Trump’s wake.

*******************************

Matthew Cebul is the lead research fellow for the Nonviolent Action Lab. Sharan Grewal is an assistant professor of government at American University, a faculty affiliate at the Middle East Initiative at Harvard, and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) alone and do not necessarily represent the positions of the Ash Center or its affiliates.

Commentary

Even with Nicolás Maduro gone, the fight for Venezuela’s future is far from over. Freddy Guevara warns that Maduro’s successors are more interested in regime survival than democratic reform.

Policy Brief

Erica Chenoweth and Matthew Cebul analyze the global surge of Gen Z-led protest movements, showing how economic insecurity, exclusion from power, and corruption are driving youth mobilization worldwide.

Occasional Paper

In this report, Matthew Cebul, Lead Research Fellow for the Nonviolent Action Lab, examines the effectiveness of nonviolent action movements in supporting democratic resilience globally. Identifying challenges faced by nonviolent pro-democracy movements, Cebul offers key takeaways for combating accelerating democratic erosion in the US and abroad.

Policy Brief

Erica Chenoweth and Matthew Cebul analyze the global surge of Gen Z-led protest movements, showing how economic insecurity, exclusion from power, and corruption are driving youth mobilization worldwide.

Occasional Paper

In this report, Matthew Cebul, Lead Research Fellow for the Nonviolent Action Lab, examines the effectiveness of nonviolent action movements in supporting democratic resilience globally. Identifying challenges faced by nonviolent pro-democracy movements, Cebul offers key takeaways for combating accelerating democratic erosion in the US and abroad.

Article

In this op-ed, Liz McKenna examines the second ‘No Kings’ protest on October 18 and offers strategies for translating successful protest movements into influential policy change. She emphasizes the importance of sustained organizational efforts alongside protest activity to engage actors across partisan lines, building a broad coalition and a durable base for the movement.