Video

Art Imitates Nation: A Conversation with Hank Willis Thomas

Artist Hank Willis Thomas spoke with Harvard professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis about how love guides his artwork at a Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics forum.

Q+A

Historical reckoning, truth-telling, and new traditions of memorialization acknowledging the legacy of slavery are all critical to moving towards restorative and reparative change says Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project Director Khalil Gibran Muhammad.

This Sunday, June 19th marks the second annual celebration of Juneteenth as a national holiday. Though the celebration commemorating the end of slavery is a relatively new addition to the federal calendar, it has been observed in Texas since the late 1800s. As the U.S. continues to grapple with structural racism and deep inequities, Juneteenth’s over 150-year history serves as a reminder of the long legacy of slavery and continuing fight for racial equality.

To better understand the role of celebrations like Juneteenth and the broader need for historical reckoning, we sat down with Director of the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Ford Foundation Professor of History, Race and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, to discuss how by starting with history, we can begin restorative and reparative work.

Ash: Over the past two years, we’ve seen a tremendous groundswell in advocacy and activism around antiracism, as well as backlash. How important are historical reckoning and accountability to the ability of antiracist work around institutional norms and structural change to succeed?

Khalil Gibran Muhammad: All forms of knowledge are historical. No field of academic inquiry or applied scientific knowledge is likely to yield successful results without knowing what has come before. Every institution and organization has a history and gains a sense of purpose by situating itself in time. The key issue when tackling structural and institutional racism is choosing to acknowledge whether and how the past accounts for inequities in the present. That’s the reckoning.

Next comes accountability. And depending on what an organization or society finds, the next step is being accountable for changing norms, policies, and practices. In the United States, many aspects of our economy, political system, and social policies have been shaped by racial and gender-based hierarchies. Reckoning with these hierarchies is a fundamental, and often a first step towards transforming our society.

The legislative backlash to teaching in schools or at work about the history of and continuing race and gender-based discrimination is a powerful demonstration of what’s at stake. The fact that most Americans are poorly educated about these issues has socialized them to accept high levels of inequality. They are not taught to see how structures narrow or expand opportunities for individuals. If history were to change, people would likely be less tolerant of structural inequities.

The Institutional Antiracism and Accountability (IARA) Project is researching examples of truth-telling and harm repair, such as truth commissions and tribunals, from around the world. What lessons have you learned thus far about how communities can effectively reckon with and heal from racial, religious, or ethnic conflict?

One consistent theme that keeps coming up is narrative or truth-telling and education. Defining a clear, accurate, and accountable narrative about the violence and harm that occurred in society, and ensuring that there are specific policy-based interventions and funding to ensure that this narrative will be incorporated into curricula, as well as memorialization and monuments.

In Rwanda, we met with the leadership of the Kigali Genocide Memorial where they run training programs for Rwandan youth, as well as youth in other countries similarly trying to understand the historical origins of systemic oppression. The Memorial was inspired by various efforts around the world to memorialize the victims of the Nazi Holocaust. It is a gravesite for 250,000 of the nearly 1 million Tutsi killed in 1994. It serves as both a site of memory and mourning for thousands of survivors, as well as a hub for national peace training programs which work towards equitable dialogue that exposes the truth rather than buries it and prepares young people to be civically engaged and vigilant guardians of peace, rooted in justice and a commitment to never repeating the past.

In Belfast, we spoke to several people who do legacy work to ensure that the factors that led to anti-Catholic violence in Northern Ireland in the 1960s, and which evolved into a paramilitary ethnic conflict known as the Troubles, are not forgotten. Healing Through Remembering is one of many organizations that promote storytelling, memorialization, and truth recovery. As in Rwanda, leaders insist that various forms of truth-telling are the most important factor in keeping the peace and building a healthier society.

Given the scale of the problem, Juneteenth is a small gesture, a hint at the possibility of change. But without a national commitment to historical reckoning, truth-telling, and new traditions of memorialization, the present and future will rhyme with the past.

How does Juneteenth contribute to US historical reckoning with slavery? Have you seen holidays and celebrations used in other countries and communities as a means to advance accountability?

Juneteenth National Independence Day is one year old as a national holiday, although it has been celebrated in Texas since 1867. Before the federal holiday, 47 states officially acknowledged the holiday. In the midst of a national period of renewed racial violence, intolerance, and legislative policies to contract democratic participation by BIPOC voters, the holiday is a necessary but, at this time, insufficient intervention to meet the scale of the problem. Were the problem of slavery a generation removed rather than seven generations old, the holiday would be part of a national reckoning as is Kwibuku, the annual month-long period of national mourning in Rwanda. It began in 1995, one year after the genocide.

The United States has not only never reckoned with the history of slavery, but sizable portions of the country have also commemorated Confederate Memorial Day and honored Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, Confederate generals, with state holidays. Moreover, just as tenuous a freedom as was the news delivered to African Americans in Galveston, TX, two and a half years after they had been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, U.S. slavery evolved into legalized segregation for another one hundred years. Since the 1960s, America has incarcerated millions of the descendants of state-sponsored oppression, and subjected them to various forms of human rights abuses.

Given the scale of the problem, Juneteenth is a small gesture, a hint at the possibility of change. But without a national commitment to historical reckoning, truth-telling, and new traditions of memorialization, the present and future will rhyme with the past.

This year’s Truth and Transformation Conference, IARA’s annual convening of advocates, organizers, scholars, students, and community members; is focused on both reckoning with the past and paying it forward. What does “paying it forward” look like in the context of historical reckoning?

Understanding and acknowledging the history of slavery and its enduring impacts in the United States will enable us to move forward more intentionally and diligently. It also recognizes that the past cannot be changed, so attention toward a future will need to include reparative work.

Members of the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Initiative team contributed to this Q+A.

Mural titled “We Are Here” by VivaLaFreedpdx, Alex Chiu, A’Misa Chiu, Justin Phillip, Kiana Chelew, Layna Lewis, and Ameya Marie Okamoto. Photo attributed to Chris Christian (under a Creative Commons, CC BY-NC 2.0 license).

Video

Artist Hank Willis Thomas spoke with Harvard professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis about how love guides his artwork at a Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics forum.

Feature

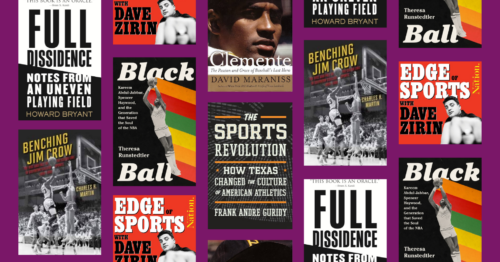

This reading list from the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project explores the intersection of sports and racial justice, in the lead-up to their panel on March 19.

Feature

The best of the Race, Research, and Policy Portal (RRAPP) this year

Video

Artist Hank Willis Thomas spoke with Harvard professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis about how love guides his artwork at a Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics forum.

Feature

This reading list from the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project explores the intersection of sports and racial justice, in the lead-up to their panel on March 19.

Feature

The best of the Race, Research, and Policy Portal (RRAPP) this year