As efforts spread across a swath of states to restrict voting access following unproven allegations of widespread non-citizen voting and other unsubstantiated claims of fraud following the 2020 presidential elections, several cities have taken an opposite approach to non-citizen voting. These cities are working to give, or more accurately restore, the franchise to noncitizens in local elections.

“One of the most common objections to non-citizen voting is that this violates the tradition in that the right to vote has always been confined to citizens,” said Alex Keyssar, Matthew W. Stirling, Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and a noted scholar on the history of voting in the U.S. “The fact is that assertion about the history simply isn’t true. Our history is much more complex, and there have been periods in places when non-citizen voting was common.”

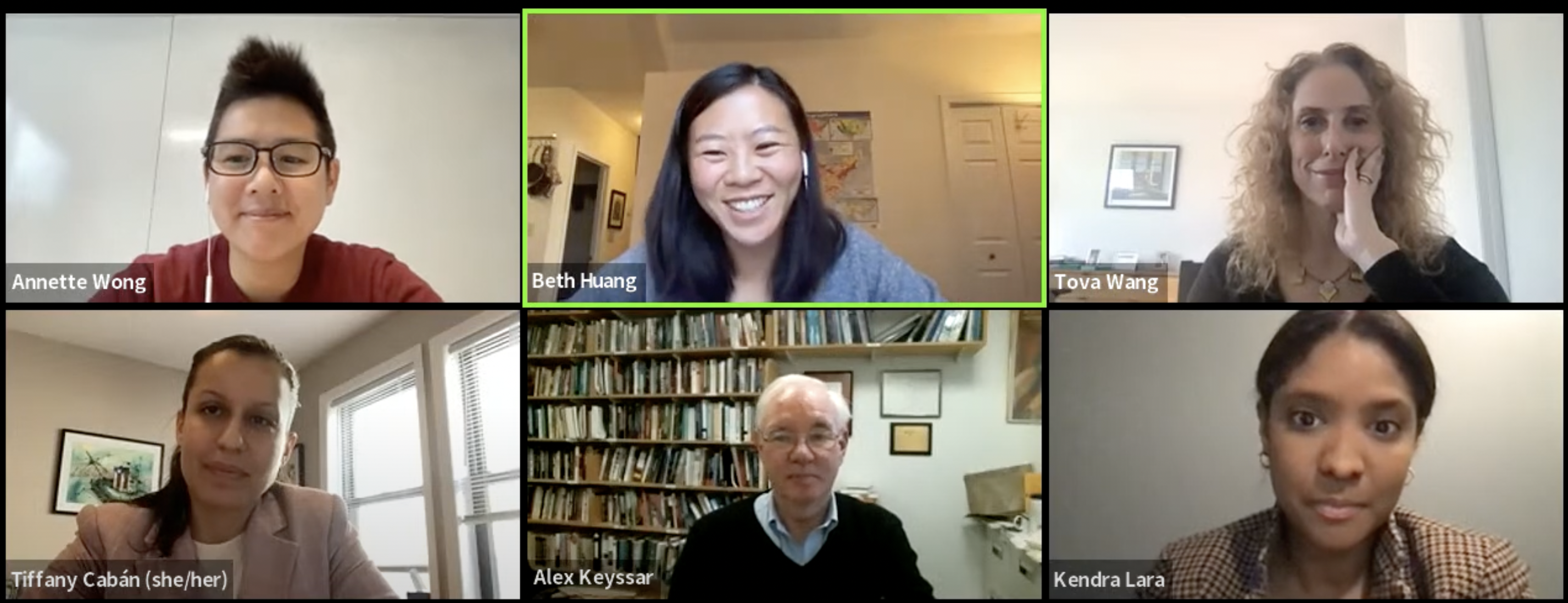

Keyssar’s remarks came during a panel organized by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation and the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston examining the nascent movement to expand the franchise to noncitizens in Boston and other cities around the country. Responding to a prompt from moderator Beth Huang of voter engagement and grassroots organization Massachusetts Voter Table, Keyssar estimated that in the 19th century, upwards of two dozen states made provision for non-citizen voting. “They wanted to increase their population, their tax base and they thought it’d be attractive to potential immigrants to know that they didn’t have to wait five years to become citizens.” By the 20th century, as anti-immigrant rhetoric began to take greater hold across the country, one by one these state laws allowing noncitizens to vote were gradually repealed.

For Annette Wong of Chinese for Affirmative Action, a San Francisco-based Chinese American civil and political rights organization, non-citizen voting held a slightly different appeal. “With Trump on the ballot [in 2016], we really were hoping to encourage people by saying, you know, this is a step to take hold of power rather than falling into panic. So, power, not panic. In these moments when we’re hearing all this xenophobic narrative coming from the right, we emphasized the expanding of democracy and access to democracy.”

Wong was referring to a 2016 ballot proposition that made San Francisco the first major US city in recent memory to allow non-citizens to vote in certain municipal elections. San Francisco expanded voting rights to all guardians or legal caregivers of children living in the city by allowing them to vote in school board elections. The measure was credited with helping to spur turnout in the city’s hotly contested school board recall vote earlier this year.

Voting and immigrant rights advocates hoped to build on the successful passage of San Francisco’s non-citizen voting rights ballot proposition by working to pass an even more expansive version of non-citizen voting in New York City. Even in immigrant friendly New York, it wasn’t an easy sell. “You had people who signed on as sponsors, and then all of a sudden, they were on the floor speaking against the bill, which is not a normal thing at all,” noted New York City Councilmember Tiffany Cabán, who represents an immigrant-rich swath of Queens and was a prime proponent of recently passed legislation to allow non-citizen voting in municipal elections in the nation’s largest city. The New York proposal, which was signed into law earlier this year, allows any immigrant with work authorization to participate in municipal elections, which is expected to expand voting rights to nearly 800,000 New Yorkers.

In Boston, non-citizen voting has taken a more circuitous path than efforts in New York and San Francisco. Enacting legislation like New York’s would require the signoff of governor and state legislature, in addition to the approval of the city council. An effort to get the council on board with non-citizen voting failed by a single vote in 2007, but advocates have kept up the pressure with hearings and other activities to continue building support for the idea.

“I gave my maiden speech on expanding the electorate and deepening democracy,” said Boston councilmember Kendra Lara. This idea of giving the municipal right to vote to people with legal status here in the city of Boston comes as a part of a larger vision to deepen the democratic process,” she added. “If government is going to be representative, particularly local government is going to be representative, then that means that everybody has to have a voice – and the way that you make sure that everybody has a voice that you enfranchise the people who are most directly impacted by the decisions that we’re making at City Hall.”

Given the likely need for state signoff to enact non-citizen voting in Boston, Lara told the audience how advocates are working hard to build a coalition of supporters to advance the idea in city hall and on Beacon Hill. The councilmember was optimistic that the tide was growing in favor of advocates arguing for non-citizen voting. “I believe we have the votes on city council… I believe that we have the votes to move it to the statehouse.”

Written by Dan Harsha and Sarah Grucza, Ash Center Communications

Watch the event recording